The Vaccine Blog

youmevaccines@gmail.com

youmevaccines@gmail.com

HPV, HPV vaccination, and opinions towards reproductive medicine

In this post, I'll go a little more in-depth into a topic I've touched on before as it sparked significant interest. HPV. However, I won`t only discuss HPV and the vaccinations themselves as medical concepts. While these are absolutely important and I will discuss them, it’s crucial to discuss how they've shaped perspectives and therefore our culture around reproductive medicine.

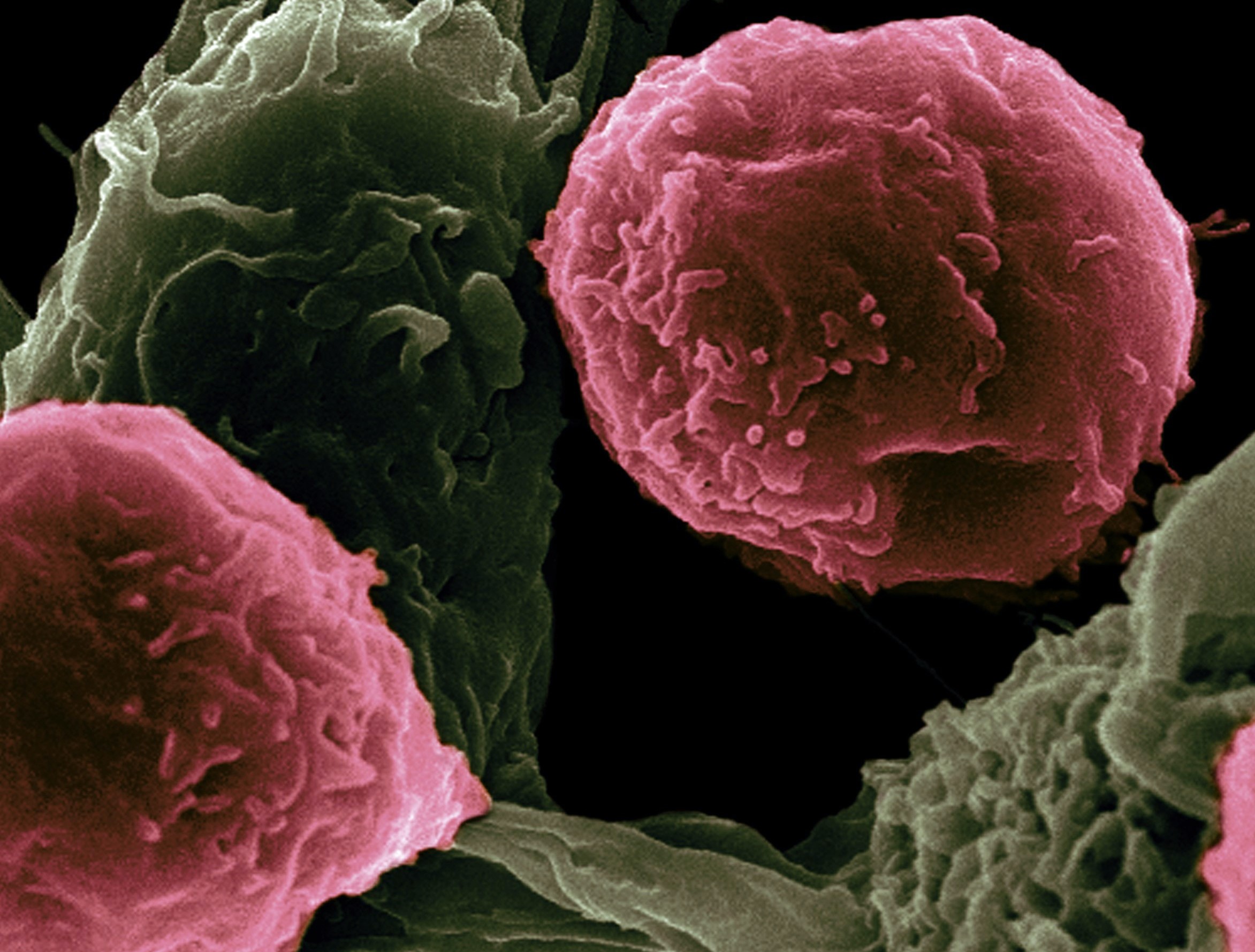

HPVs (Human Papillomaviruses) are a subgroup of more than 200 viruses. It is a very common sexually transmitted infection; however 90% of infections resolve and do not progress to cancer. They can be subdivided in high risk and low risk types; the former including HPVs 16 and 18; the latter HPVs 6, 11, 13, and 32. This subgrouping is based on the risk that they will cause precancerous growths (ie. warts) or various types of cancer in infected individuals (particularly cervical cancer). In terms of treatment; 3 vaccines have been developed. Gardasil; Cervarix, and Gardasil 9.

Gardasil has been licensed in the US since 2006 for males and females between ages 9 and 26 for the prevention to cervical cancer and precancerous lesions ie. genital warts. According to the website of the European Medicine Agency, it was granted authorisation valid throughout the EU on 20th September 2006. It is a quadrivalent vaccine; meaning that it protects against 4 HPV strains linked with cervical cancer. These are HPV 6,11,16, and 18, which are responsible for cervical cancer, cervical adenocarcinoma, intraepithelial neoplasias of the cervix, vulva, and vagina, as well as genital warts .

Cervarix has been licensed in the US since October 16th, 2009 for women and men aged 9 through 25 years of age. The European Medicines Agency granted Cervarix a marketing authorisation valid throughout the EU on 20th September 2007. It is a bivalent vaccine; meaning that it protects against 2 strains of HPV; 16 and 18. These are the two strains most commonly associated with cervical cancer and anus, as well as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia of the vagina, vulva, anus, and cervix.

According to the website of the FDA (food & drug association), Gardasil-9 was approved in 2014 by the FDA. In the EU, the European Medicine Agency granted Gardasil 9 a marketing authorisation valid throughout the EU on 10th June 2015. When distributed, it protects the same 4 HPV strains above; plus an additional 5. Thus, it covers nine HPV strains; 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58. It is indicated (or approved) for males and females from the ages of 9 through 45 for the prevention of a variety of cancers and precancers linked with HPV. These include cervical, vaginal and vulvar cancers (in women), and anal, oropharyngeal, and other head and neck cancers, as well as genital warts in both men and women.

As of 2020, HPV vaccination programmes have been introduced in over 100 countries; which is just over half the world's countries. Further, according to the website of the CDC, in the US alone, 33,700 cases of cervical cancer can be prevented each year by HPV vaccination. “In May 2018, the WHO Director-General announced a global call for action to eliminate cervical cancer, underscoring renewed political will to make elimination a reality and calling for all stakeholders to unite behind this common goal.”

These are huge achievements and ambitions; which have benefitted lives on a huge scale globally, and undoubtedly will continue to in the future. That said, the large picture is only one aspect of HPV vaccination. The other element of it is the individual level. To really appreciate the impact vaccination has on lives; we need to look at the individual level. That's what I'll do in the next section

Ana was diagnosed with Stage 2 cervical cancer at age 35, as a single mother with 2 children, ages 6 and 8. She had abnormal Pap smears consistently over an 8 year period, however tests always returned clear. After abnormal bleeding, she had further testing. Three days before the Christmas break at the school she taught at; she received the call from her doctor that would change her life. She had cancer.

For six weeks, she endured weekly chemotherapy and 28 rounds of external radiation, followed by 3 more rounds of internal radiation. She says that “my body was exhausted.”After the treatment was complete, Ana experienced significant discharge. Her doctors advised her not to be concerned; however after this continued over a period of time Ana realised she had to seek a second opinion. The second doctor confirmed her worst fears - there was residual cancer. Two weeks later, she had a radical hysterectomy (ie. complete removal of the uterus, cervix, and part of the vagina. Following this, there was no evidence of cancer.

However, it wasn't over. Several days later, she experienced extreme kidney pain, and it turned out that the radiation had damaged the ureters on both sides of her body. She endured major reconstructive surgery on her bladder and ureters; as well as a catheter and stents in both ureters to aid healing. She has now been cancer free since January 2018; and wants women to know to take care of themselves. Her mission is to share her story so others do not have to experience what she did. That is the power of HPV vaccination, and of vaccination more broadly.

Despite the remarkable impacts these vaccines have had on people's lives; stigma has always been attached to reproductive health.There has been concern that HPV vaccination encourages promiscuity, and disregard for sexual health. The first thing I`ll say is that the concern can be understood; the majority of sexually active people will contract at least one HPV type throughout their life. It's crucial to acknowledge these concerns before trying to refute any claims. HPV itself as well as other STDs, unplanned pregnancies, and the myriad of other issues that come with being irresponsible around sexual health do warrant concern. This is especially true for (some) teenagers and perhaps young adults who don't fully appreciate how severe these consequences are. And it's easy to make assumptions about such individuals; and why they have this disregard. The first (and most obvious, I think) is that they don't have enough life experience. Alternatively, they don't have the right life experience; and this can apply to anyone regardless of age. What I mean by that is; if someone hasn't had experiences with life changing health conditions they're less likely to think about how decisions they make could cause them. Some people grow up in environments that make them vigilant of decisions to some degree; others don't. Maybe they socialise with people who have values that prioritise conscientious decision making. The point is; experience brings wisdom not necessarily knowledge or age. Of course increasing both of those variables makes wisdom more likely - but not guaranteed.

That said, the assertion that HPV vaccination causes disregard for STDs and other sexual health issues is not supported by literature. For example, a 2019 paper by Brouwer and colleagues found that, in their own words, “HPV vaccination was not significantly associated with an increased likelihood of sexual debut, decreased age of sexual debut, nor an increased number of sexual partners.” This applies to both men and women. They did, however, find that race and alcohol use did predict sexual behaviour. Not only this, but a 2015 study by Leah Smith and colleagues found “strong evidence that HPV vaccination does not have any significant impact on clinical indicators of sexual behaviour among adolescent girls.” Also, the results suggest that “concerns over increased promiscuity are unwarranted and should not deter from vaccinating at a young age.”

Regardless of the literature; let's think about this for a moment. If one genuinely does not care about sexual health - why seek out a HPV vaccine in the first place? Why seek out vaccines or treatment for any STD, for that matter? Those spending time, effort, energy, and money on vaccination are most likely to be conscious of health in a more holistic sense. People generally only spend these resources on things they really value - someone spending them on health clearly values it. I would say that this appeals to common sense; and this is actually one of the best ways to test if many assertions are true. Does it appeal to your common sense?

However common sense is difficult to apply to topics that are emotionally difficult. That's my own experience anyway. It's relatively easy for one to say “use common sense”, when they themselves are not in crisis, or even feeling emotional at all. From the other individual`s perspective; the situation may be completely overwhelming and induce huge anxiety. It's very, very difficult to apply common sense in those types of scenarios. In fact, I`d argue that it`s even impossible in more severe circumstances.Of course, we can learn to emotionally regulate, but that may only work to a degree. Maybe someone is in a situation where their core values are compromised. Perhaps they`ve invested significant time, energy, money (or perhaps all of these) into raising a child or attempting to become pregnant. Perhaps they saw misinformation or disinformation about the HPV vaccine online, heard it from friends, or got it from another source. Perhaps the misinformation falsely asserts that the HPV vaccine impacts fertility. Now there is a seed of doubt planted. There is real worry now. Maybe they hear it again, or even several more times; the doubt is now beginning to grow. This of course depends on many variables including their pre-existing knowledge about HPV and the vaccine, their perceived risk of contracting HPV, and many others. The point is; eventually the time will come to take the vaccine. Now, if there is any degree of doubt, no matter how small, this can make it very difficult to accept it with certainty. Why? If, as I`ve said, they've invested significant resources into attempting pregnancy, they generally won`t want to accept anything that has a chance of compromising that.

Also there is another important element of this that may influence perceptions; stigma. No area of health is as stigmatised as reproductive health; although there is increased dialogue about there area recently. For that reason; some patients might be reluctant to breach the topic of HPV vaccination with their physicians or other healthcare providers. This is particularly true if they are a new patient and haven't yet established a rapport with the physician/HCW. Further, add in the fact that vaccines themselves are stigmatised. Now you have the potential for patients to find it extremely difficult if not impossible to confidently and comfortably discuss these issues with anyone; let alone healthcare professionals.

That said; stigma doesn't have to be about HPV necessarily; it can be other STDs too. Take any aspect of reproductive health; be it fertility issues, methods of contraception, unplanned pregnancies; and so on. The next logical question is; well, health issues are difficult enough to discuss - why is reproductive health in particular so stigmatised? I'd argue that it`s one key word; vulnerability. I`ve said this before, but it's worth repeating. We`re vulnerable when we`re with healthcare providers; maybe more vulnerable than we'll ever be with the majority of people we know, That`s emotive enough. However, add to it the element of fertility; and the fact that having children is a major goal for many people from when they are very young.Although, that culture is changing (1 in 5 American adults now do not plan to have children), it is still a core component of life satisfaction for many people. As the statistic shows, despite the increase in childlessness, the motivation to be parents is still very much the norm. Regardless of which decision one makes; we can see that reproductive health is an important aspect of health freedom for the majority of people.

According to the website of the World Health Organization, “the number of women desiring to use family planning has increased markedly over the past two decades, from 900 million in 2000 to nearly 1.1 billion in 2021 Between 2000 and 2020, the number of women using a modern contraceptive method increased from 663 million to 851 million. An additional 70 million women are projected to be added by 2030. Between 2000 and 2020, the contraceptive prevalence rate (percentage of women aged 15–49 who use any contraceptive method) increased from 47.7 to 49.0%”

Dialogue around HPV (and reproductive health more broadly) has only recently become normalised around this in society. Despite this, it has always been an integral aspect of health. In 1988, the phrase “reproductive health” was first coined by the World Health Organization`s Special Program on Human Reproductive Research; and was finalised in 1994. An article published on theconversation.com on June 21st, 2018 describes how the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals -– introduced in 2015 –- were created to address many issues faced by women in relation to reproductive health. For example; every year over 30 million women in developing countries don't give birth in health facilities. Further, over 45 million women receive inadequate antenatal care; and sometimes even no antenatal care at all. Further, over 200 million women do not have access to contraceptive methods despite wanting to practise family planning. The goals recognise that sexual and reproductive health and rights are fundamental to people’s health and survival, to gender equality and to the well-being of humanity. Not only this; but in a bid to boost these fundamental rights, the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights was convened in 2016.

Conclusion

Therefore, there is clearly an increasing appreciation for reproductive health and the important role it plays in people's lives around the world. The numbers of people using family planning methods and the increased dialogue around HPV really reflect this.

That said, there is still progress to make; and the stigma and perceptions of HPV vaccination also reflect that. However the progress already seen shows that we as a society can develop the tools and skills to further reduce stigma and improve health. Thanks for reading

References